Adana refugee camp - March 2022

Text by Fabio Geda

Photographs by Paolo Messina

This is my first visit to the camp. I'm leaving with Arianna and Paolo. In the days before departure I read a lot in order to understand where I am going. I stumble upon several UNHCR appeals asking the world not to forget refugees and displaced Syrians eleven years after the start of the conflict. I find out that Syria is the most serious world crisis for number of people forced to flee. Over 13 million elderlies, women and children have fled the country or are displaced within its borders. Neighbouring countries took 6 million refugees and over half are in Turkey, on the outskirts of cities or in places like the spontaneous camp that SSCh have been taking care of for years.

Girls pumps out water from the first well that SSCh dag in 2018. The second well is nearing completion.

Here, one thing I like is the clarity with which SSCh, knowing that they cannot help everyone, they have chosen to help someone. Their stubbornness with which they take care of this tent city (6000 people of which 4000 minors) is growing year after year in competence and operations in an ever more precise and effective way. They chose a piece of the world and try to make it better with a pragmatism that convinces me. What do I mean? They are aware of not possessing magic wands. And we know that people are more willing to intervene when the goal is to solve the problem permanently, to take someone away from degradation forever but they can't be bothered when they need to stand in degrading conditions next to those who suffer, being satisfied with reducing the suffering because eliminating it is not possible. To do this it takes courage. And it takes wisdom.

Arianna Martini (president of SSCh) while waiting for food distribution

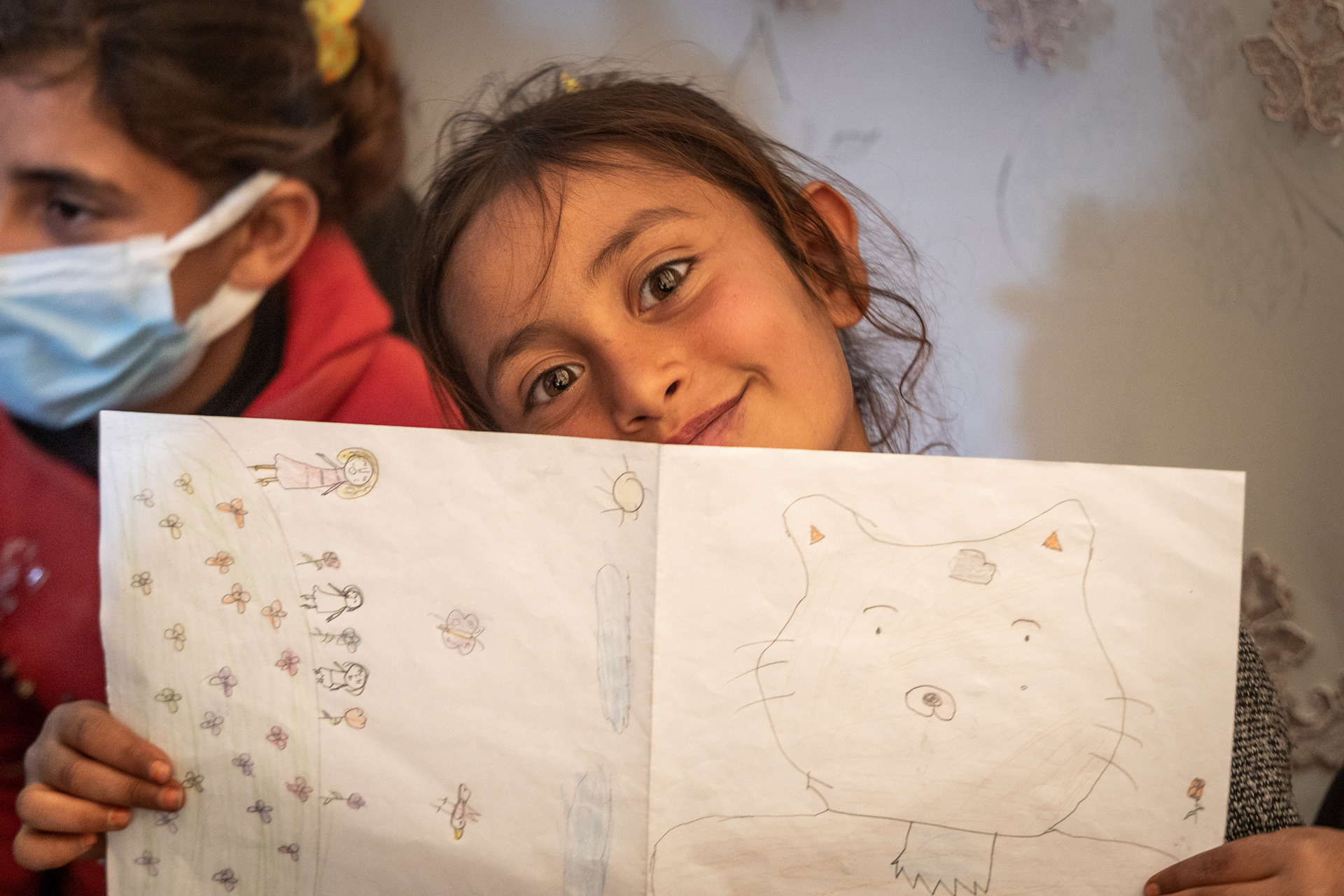

There is a lot to do at the camp. You walk among the tents and are surrounded by girls and boys: some scrutinize you buzzing from a distance, others queue up, some take you by the hand. Pre-teens seek attention with the gaze, and when you hook it there are those who hold it up and those who lower their eyes. Teenagers are already men and women teenagers disappear from sight, like almost all women.

Paolo Messina tries to tell through images the complexity of the camp: men, elderlies, environments, but it is inevitable that in front of the lens, in particularly, children fall for it. Which then are the ones who make you realize the disastrous hygienic situation of the area: improvised latrines, rubbish everywhere, broken glass in the sand where they run barefoot. More terrible than living in unworthy conditions is perhaps not noticing it, and it is heart breaking to realize that there are some in the camp who have stopped doing so.

Children at play with toys made out of scraps

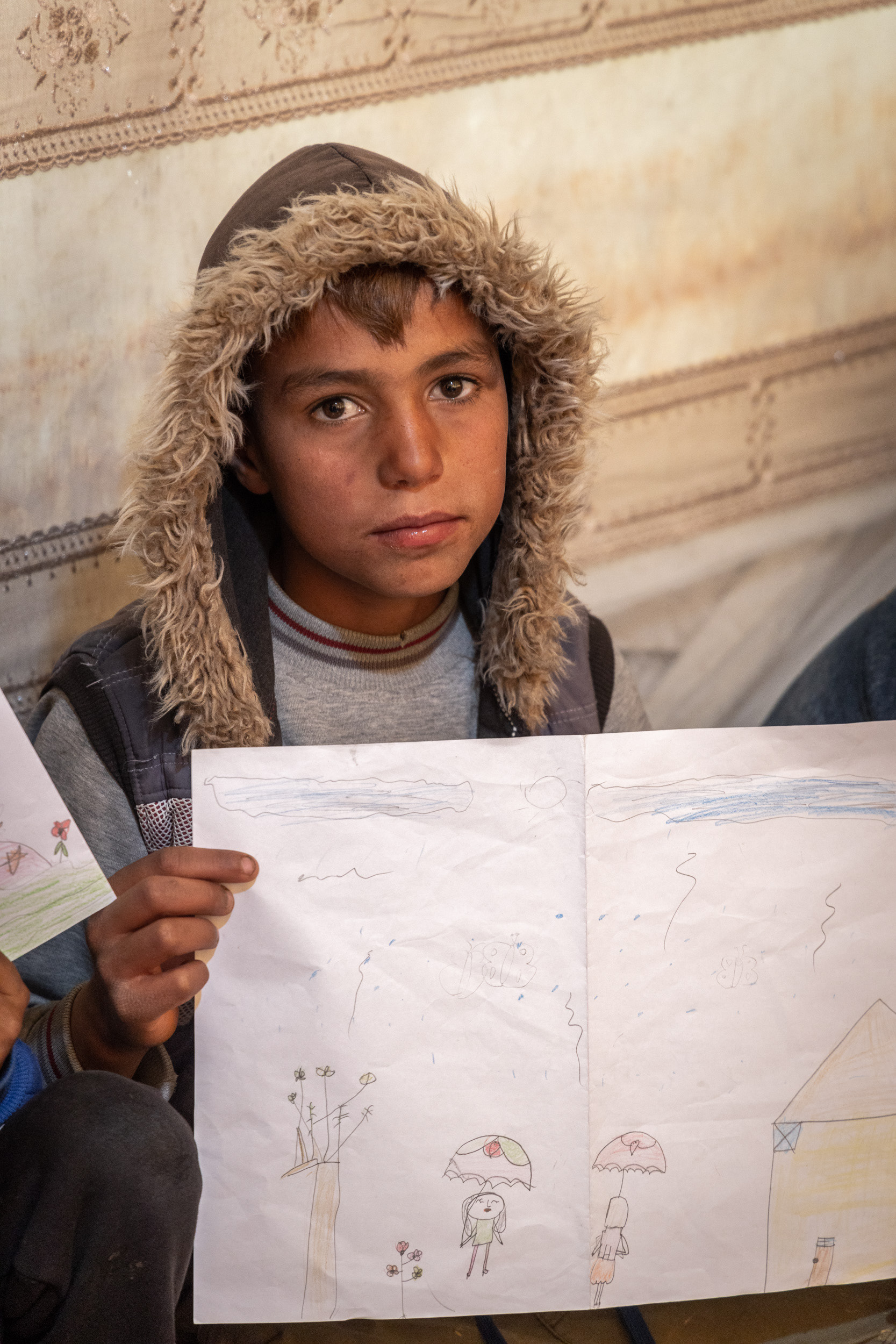

I have with me one scene in particular: Azouf, 13, chases us for two days to take us to his tent, where he lives with his sister and father, an elderly and sick man. We finally find the time to follow him.

While the father, through Yahya the interpreter, asks us for help, Azouf tries to make us tea. At some point it goes anxious because the water struggles to boil. We tell him not to worry, to leave it. He insists. And when he finally brings it to us he radiates pride everywhere.

While the father, through Yahya the interpreter, asks us for help, Azouf tries to make us tea. At some point it goes anxious because the water struggles to boil. We tell him not to worry, to leave it. He insists. And when he finally brings it to us he radiates pride everywhere.

Azuof in his tent

We spend a lot of time in the two makeshift schools, what SSCh calls "Rainbow Tents". Girls and boys attend them a few hours a week, when they are not at work in the fields, the area where they are obviously exploited without restraint. They don't attend Turkish schools mainly for two reasons: they need the little money they can earn with picking and Turkish schools don't really welcome them.

I attend a remote meeting with a school in Turin and the English lesson that Chiara gives connecting from San Diego. If the camp cannot move, the world enters the camp. And maybe they, one of these pre-teens, one of these children, will find the strength, one day to free him or herself, to leave, to go and conquer a different life. Yes, maybe they will.

Back in Turin, I spoke to everyone about this experience for days. When I stopped talking about it I started dreaming of it. Faces and places came to visit me at night.

Fabio Geda and Arianna Martini walking around the camp

In July, I'll be back. Again with Arianna and Paolo, but this time there will also be Anna (doctor) and Pep (nurse).

Fabio Geda is an author and a social promoter based in Turin, Italy. He was selected for the Strega Prize and his bestselling novel "In The Sea Thera Are Crocodiles" sold over 400.000 copies and was translated in more than 30 languages