I met Arianna last July in Italy. She is president of a non-profit organization called Support and Sustain Children, which is based in my home town, Bergamo. When I asked if I could join their future missions in one of the refugee camps in which they operate, the interest seemed to be mutual, but because of the Covid 19 pandemic we were unable to set a date.

Time went by until one day in October we spoke on the phone and Arianna asked me: “Do you want to go to Turkey tomorrow?” At least – I thought – it was still morning.

I spent the following hours doing some work, looking for flights, checking the travel regulations between Spain, Italy, Germany, Austria and Turkey since there were no direct routes.

The more I searched the more confused I got. Even the airport police in Köln couldn’t provide precise information with regards to passengers coming from Spain, directed to Turkey flying via Germany and whether I was going to be able to move freely between gates at the airport.

Eventually after one beer with friends, I booked an overnight itinerary Palma-Köln-Istanbul-Adana; a journey of 14 hours and scheduled for the following day.

I woke up the following morning with a great sense of remorse, for not stopping at the “one beer” the evening before. The day was going to be a long one, and the night even longer.

I started off by changing a flat tyre on the car before taking the little one to school. I worked up to one hour before going to the airport, packed some stuff, said goodbye to my girlfriend Anna, our daughter Nina, and left.

When I arrived at the airport, I found out that the cheaper, long-stay car park was closed, so I had to park in the standard building. Ryanair then joined in the “milking” by charging me a fortune to print out a tiny boarding pass (since the online broker I had booked with wouldn’t let me check-in online). It was like when you play Monopoly and land on Park Lane first, and then Broadwalk immediately after.

Once at Köln I got lost in a dark, deserted terminal with a fellow traveller from Mallorca while following the connection flights signs. Turkey was virtually the only country accepting people from Spain, and was his only option to have a holiday abroad. We were both trying at any cost to stay in the departure building in order to avoid any possible Covid test or – even worse – quarantine. In the end we were told to feel-free to go wherever we had to. All controls and restrictions seemed to be a media hype, perhaps too busy frightening their audiences rather than informing them.

Eventually I got to Adana right on schedule and the SSCH team eventually picked me up with some delay because of some issues with their rental car. It was six of us. After the presentations and after the cars gear shift was tamed once again we drove off.

Arianna was there and Luca – her husband – took the wheel. Back in Italy he’s a full-time gardener. They’ve been supervising the projects together since 2014.

Arianna and Luca escorted by their young friends

Sitting in front of me was Elisabetta, she was in charge of the education programs. Back home she teaches at Lorusso e Cutugno prison in Turin. She is president of Comitato Mahmud (Comitato Mahmud | Facebook) which directly supports 3 groups of orphans of the camp. She’d worked on various missions in Nepal, Sudan and Italy, and has been collaborating with Arianna since 2015.

Elisabetta greeted upon arrival

Next to her was Yahya, the field coordinator and interpreter. He is from Idlib and left Syria when the war started. He then travelled between Lebanon and Japan to continue his training as an Archaeologist. He entered Turkey to visit his dying father and hasn’t left since. He now lives in Adana with his wife, trying to make a living with the salary from SSCH and other small jobs. In his own words: “I am happy to work with SSCH because they are helping my people’s diaspora who are oppressed by this cruel war”.

Yahya helping a young girl with the well

In the back with me was Anna, the doctor. She previously worked as medical aid with the Italian Navy, on a rescue boat in the Mediterranean Sea during Operation Safe Sea. She’s also taken part in various humanitarian missions in South America. She now works as a freelancer in Bergamo – where Covid19 struck first and deadlier still in Italy earlier this year – for Giovanni Carlo Rota Foundation. She eventually contracted the virus herself.

Anna aka “Doctora” welcomed by children

After a short drive we arrived to a local chemist who was supposed to provide us with a list of medicines. SSCH is not allowed to transport drugs from Italy. The biggest problem that day was that it was closing time for pharmacies so the little brother of the shop owner had to smuggle what available from…somewhere.

The last time a doctor visited the camp was in February, just before the Covid19 outbreak in Europe, 8 months earlier. Anna was clearly disappointed when she received just a handful of painkillers and a few bottles of eye drops.

The camp is about one hour drive from Adana. It hosts about 800 families, and SSCH has been looking after its inhabitants since 2014. They are all from Syria, mostly from Hama, Idlib and Aleppo.

Sunset view of one sector of the camp

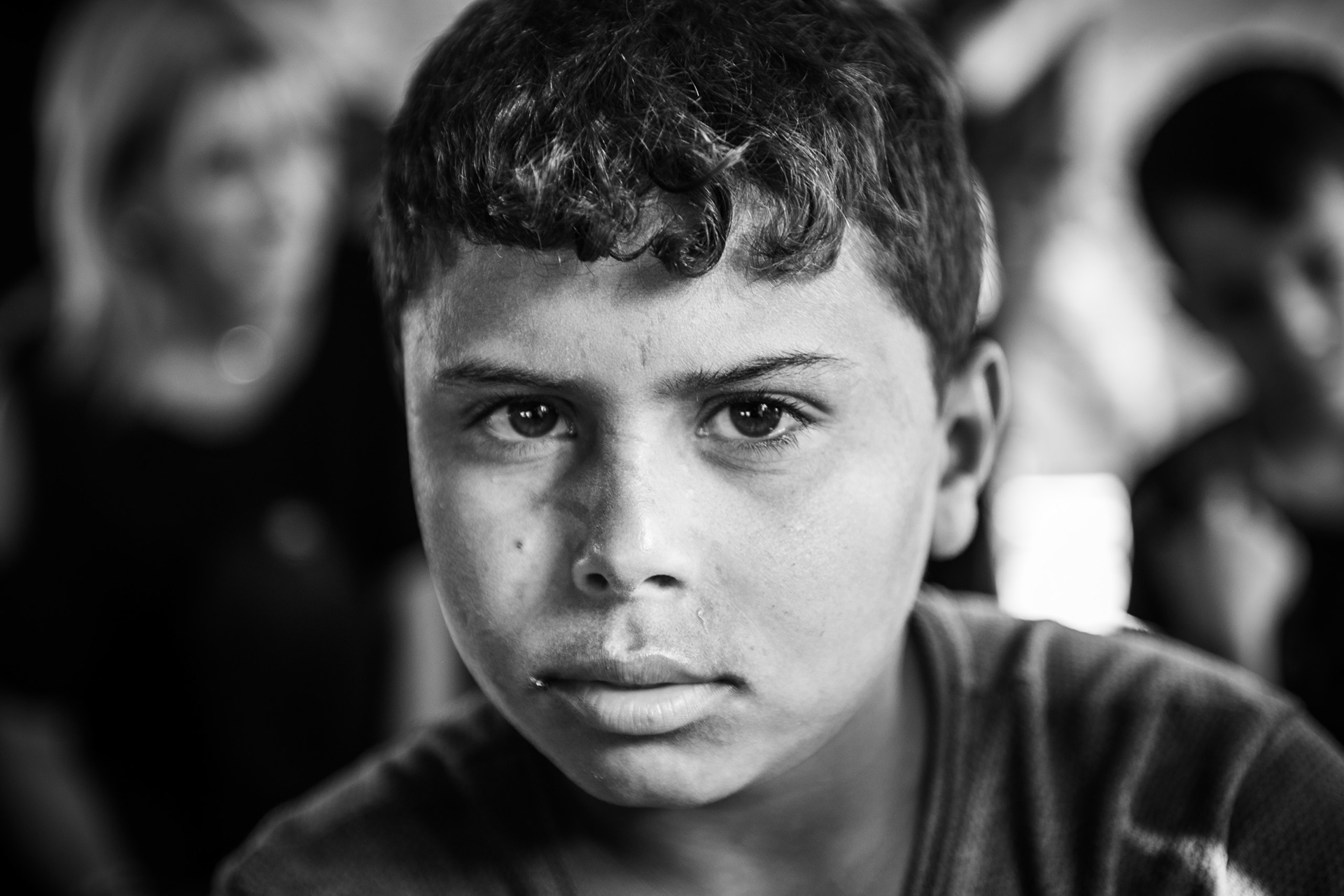

When we reached our destination we were immediately surrounded by big smiles and cheerful children.

For me it was the first time at the camp, but Arianna and the rest of the team have been watching these kids grow up. I could feel their emotion at finally being reunited with them after so long and the joy these volunteers were bringing to these people simply by being there with them was clear to see.

Soon after our arrival we met Abu Khaled, the leader of the first sector of the camp. With him, Arianna would coordinate the distribution of the food packages (pasta, rice, biscuits, tea, soap, flour, beans, sugar and oil). All goods are bought locally. The newly-dug well is also located in his courtyard, and brought a massive relief – logistically and economically – to both the refugees and SSCH.

Anna set herself up in Abu Khaled’s tent, destined to be her practice for the day and she begun to assist the families who had gathered in large numbers both inside and outside the tent.

Meanwhile, in another part of the camp, Elisabetta started with the managing of the Rainbow tent: the classroom. She was training children and their tutors – inhabitants of the camp themselves – and distributing school supplies.

Every communication was made possible by Yahya, who had to be in three places at once. A second interpreter (also a refugee from Syria) was due to travel with Elisabetta but was denied boarding at the airport in Italy.

This first day went pretty fast, and in the evening we went back to our hotel in Adana. Poor Yahya was so edgy from the stress that he went to buy some cigarettes.

After a much needed shower I wanted to save the images on my laptop. To my utter dismay the disk was full and I had no external hard drive for backup. I started to sweat again. Deleting stuff seemed to have the opposite effect as the free space was magically shrinking! I thought it was a nightmare and hopefully soon I was going to wake up but that didn’t happen. I tried to re-install the entire OS but the wi-fi was so weak that I had to give up. I asked in reception if by chance they could help me but after a few attempts to explain what I needed, I was presented a USB charger for i-phones. I felt hopeless, my only option was to buy an external HD the morning after before going to the camp – I was after all doing so well with the budget – and free space on my SD cards. Arianna might have been disappointed not having new pictures right away, but at least the material was not lost – but watch this space.

We then left for the restaurant. While walking I fiddled in my pockets and felt 2 of the 3 SD cards I had shot on. I wasn’t sure whether to be happy about it or not. After a world-famous Adana kebab we went back to the hotel; on this short 100-meter walk, black magic struck again and my SD cards were nowhere to be found. I searched for hours, alone at first and then with Yahya, and virtually everywhere we had been, but all to no avail. All the pictures I’d taken of the second half of the day were gone forever. I hoped once again to be having a nightmare within the nightmare but it was all real. It did happen, I lost the pictures, possibly some of the most significant portraits I had ever shot. I decided to do a quick edit of the only card left. I took the camera out of the bag and – of course – I dropped it, pulverizing the UV filter. Honestly, I couldn’t care less at that stage. I would have happily given all my gear away if that would have brought the lost images back.

I begun the edit on Lightroom CC via a camera-to-phone connection, so that I could at least share something rapidly by morning. I didn’t know then that the program was set by default to use cellular data and sync to the cloud. It was going to max out my 4G allowance and cost me another stop on Park Lane in roaming charges.

That night I went to bed feeling lost, sad, guilty and generally bad.

In the morning two things put me back on my feet. First it was magic striking once again. My laptop suddenly had 50GB of free space available. Second but probably more important was the support and sympathy I got from the team. My pictures were lost but not me any more. Eventually what I had on the first card saved the day.

We drove around for a couple of hours to get more supplies. I can’t recall precisely what and where as I was glued to the monitor of my laptop, trying to catch up with the editing.

Once at the camp, I photographed mostly orphan groups, for the distribution of vouchers that allow the refugees to buy food in a store in Adana.

Group “number 1” is perhaps one of the most serious cases since these orphan siblings have no adult responsible for them at the camp

Anna and Elisabetta set themselves up in their respective tents stationed in the other sector of the camp, and where they were going to spend the entire day in unbearable temperatures.

Later on, Arianna received a new – although recurring – disturbing text message by an anonymous sender who once again launched a series of defamatory accusations and threatened to call the police. It’s most probably another attempt of extortion.

The camp is situated on private agricultural land, and there’s always the risk that the landowner might decide to revoke his permission despite the refugees paying rent for it. They also provide an extremely cheap source of manpower. Children are not spared and find themselves having to choose between school or slaving off in the fields to support their families.

Unfortunately it’s not news anymore, that desperate migrants all around the globe end up being used as modern-day slaves to fill in the gaps of low-cost labour so much needed by our sick economy. This “meat market” blossoms at every exodus in which refugees are left to themselves to face perilous journeys – often exploited by local mafias – from war-torn countries or dystopian governments. It’s a Darwinian struggle where only the fittest makes it to the shores of the supposedly safer and more prosperous western countries but they’ll often discover though that the promised land is actually an impenetrable fortress.

The people I saw in the camp have many horrific stories to tell, and they’d only barely managed to save their own lives. They are not even the bottom of the pyramid, they are crushed beneath it.

Monday morning arrived quickly, and Anna, Elisabetta and I were supposed to fly back home. Anna woke up with 39°c fever and flying was just not an option. A high dose of paracetamol lowered the temperature to just 0.1 degrees below the limit for travelling and luckily never rose again during her 4-connection-20-hour flight back to Bergamo. It must have been a case of exhaustion.

I wonder – paraphrasing – when doctors, nurses and all the people who dedicate their lives helping others will start receiving a louder applause than football players and celebrities – let alone a better salary.

So why do they still do what they do? Is it in their nature? Was solidarity included in Darwin’s theory of evolution?

I can’t answer these questions but I see the consequences of such altruistic reality something like a drop in the ocean that maintains its own properties, its own identity and its own mission, no matter what.

One drop, two drops, three…infinite drops.

The force of the water does not stop at the surface you see. Every effort, every action we do (of which we will maybe never see the direct effect) falls like a drop among the many to form a sea, a sea of change.

Please donate and engage www.supportandsustainchildren.org